Most people are not aware that there is a difference between vellum and parchment – both being animal skin (not pretend ‘parchment' paper). The names of skins are often used interchangeably and it can be quite difficult when looking at mediæval manuscripts to determine whether the substrate is vellum or parchment. The clue is often the crispness of the letter-forms, but if a sharpened quill is not used in the first place, then this can be even more challenging! I prefer the terms that the makers of vellum and parchment use and so regard vellum as calfskin; it is a dream surface to work on when prepared properly. Parchment is sheepskin and, in many people's opinion, is inferior to vellum for calligraphy. Goatskin can also be used but its surface is often very bumpy. The skins are a by-product of the meat industry, and as far more skins are produced than can be used by the leatherworkers, many skins end up in land fill.

Vellum, a word that is used loosely to mean parchment, and especially to mean a fine skin, but more strictly refers to skins made from calfskin (although goatskin can be as fine in quality). The words vellum and veal come from. The Original Writing Materials Parchment is animal skin (such as sheep, goat, cow, hare, horse, or deer) specially prepared to be used as a writing material. Vellum is made specifically from the skin of a calf specially prepared to be used as a writing material or to create book covers. Historically speaking, calfskin has been the finest parchment available, so people have long referred to refined parchment as vellum. Here's a simple formula: All vellum is parchment, but not all parchment is vellum. Leather refers to the same raw material — animal skin — that has been chemically altered to render it impervious to rot.

To see more about vellum and parchment and the qualities of the skin, what to look for, types of skins and the best to use, see my Calligraphy Clip, vellum and parchment.

Skins for both parchment and vellum are selected carefully, washed and soaked in lime to slightly swell the hair follicles so that the hair can be removed more easily. The skins are washed again and then stretched out on a ‘frame' or ‘herse'. Whilst on the frames they are kept under constant tension and scraped with a semi-circular razor-sharp knife. Lee Mapley of William Cowley Parchment Works, finalist in the Craft Skills Awards, is shown on the right; he produces skins of excellent quality. The skins are then allowed to dry and when ready, cut from the frames and rolled, stored and then sent out.

******SPECIAL OFFER!! Three pieces of skin for £12 (+ p+p), usually £16 (+p+p). I always use skins from William Cowley, the only parchment and vellum maker in the UK, and I highly recommend their products. They have kindly agreed to a special trial offer for subscribers to my newsletter. R cran. A whole skin is very expensive, so why not try manuscript calfskin vellum, classic vellum and sheepskin parchment (*see next but one paragraph). All three pieces are about 5 x 3 inches (approximately 13 x 8 cm) which will be big enough to write out a verse of a short poem, piece of prose or paint a mediæval miniature (and without the hole as in those shown here!). To get this offer, please email me at the address on my website. I will then give you a personal code and the website link to William Cowley. They will give details of payment and ask where to send the offer. This offer is available to all my subscribers, and William Cowley will advise on postage for non-UK addresses.

*******The Private Library, the journal of the Private Libraries Association, has produced a whole edition on vellum, featuring a fascinating, detailed article about many aspects of skin written by James Freemantle. It costs £6 for UK residents (£5 + appropriate p+p for non-UK) and is available from Jim Maslen at maslen@maslen.karoo.co.uk

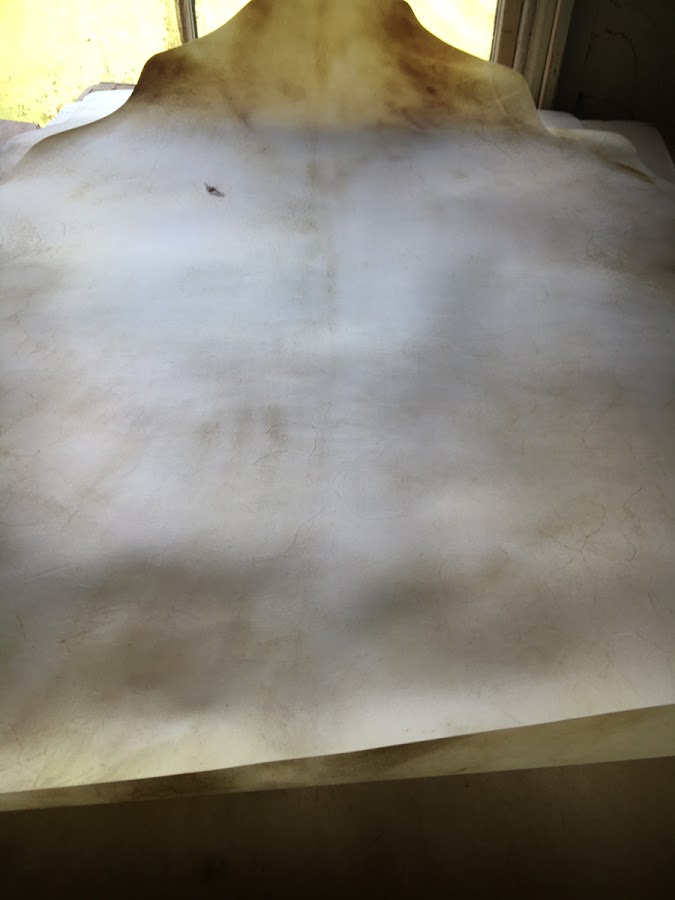

Vellum skins are not the same thickness all over as is paper; this can be seen from the picture on the right. This was the skin that I produced for the British Library's major Genius of Illumination exhibition. The haunches, spine and shoulders are thicker and the ribs thinner. Care must be taken when selecting the part of the skin to use as parts will move and buckle or cockle in heat or when damp.

Parchment Animal Skin

*There are also different types of vellum skin. Calfskin manuscript vellum is prepared on both sides and so can be used in books or where you want to use the back of the skin. Classic vellum is bleached but prepared on only one side – useful if you want to create a broadsheet. Natural vellum is not bleached, shows the character of the skin, and again prepared on only one side. Kelmscott vellum has a surface coating which makes it ideal for printing; it was made originally for William Morris's Kelmscott Press. It's good for painting, but you need to use a dry-ish mix of gouache to avoid lifting the special finish. Slunk vellum is from the skins of stillborn or uterine calves and is quite thin but still strong. You can see the thinness in the picture as the handle of the paintbrush shows through much more in the skin on the far left.

The skin needs to be prepared before use for writing and painting, and this information is in my book Illumination – Gold and Colour– and the accompanying (and stand alone) DVD Illumination, which is over 3 hours long. Both include how to stretch vellum over board to avoid it buckling and cockling and how to gild and paint a mediæval miniature in the traditional way. There's lots of information about tools and materials for Illumination, as well as projects which are very simple to make.

Vellum skin does, though, give the most wonderful surface for writing and painting, and if you've never tried it then you are missing a rare treat!

Vellum is a high-quality form of parchment. Originally, it meant calfskin, but in English the term is used more widely.[1]

Like parchment, the skin is prepared to take writing in ink.[2] It was one of the standard writing surfaces used in Europe before paper became available. It continued to be used for high-status documents. The vellum was used for single pages, scrolls, codices or books.

To manufacture vellum, the skin is cleaned, then bleached, stretched on a frame called a 'herse', and scraped with a knife. When vellum is scraped, it is by turns wet and dry to create tension. A final finish is got by rubbing the surface with pumice, and treating it with lime or chalk. Then it is ready to accept ink.[3]

Modern 'paper vellum' (sometimes called vegetable vellum) is made out of synthetic material instead of mammal skin, but is used for the same purpose as normal vellum.

Use in the past[change | change source]

In ancient Europe, vellum meant good quality prepared animal skin. Calves, sheep, goat and even camel are known to have been used to make vellum. The very best vellum was made from unborn animals. It can be hard to identify the animal used to make old vellum without using a science lab.

French sources defined velum (or velin in French) as made from calves only.[4] This has remained true in modern times.

Usage[change | change source]

Most of the best sort of medieval manuscripts were written on vellum. Some Buddhist texts were written on vellum, and all Sifrei Torah texts are written on vellum or something similar.

A quarter of the 180 copy edition of Johannes Gutenberg's first Bible printed in 1455 was also printed on vellum, presumably because his costumers expected this for a high-quality book. Paper was used for most book-printing at the time.

In art, vellum was used for paintings, especially if they needed to be sent long distances, before canvas became widely used in about 1500, and continued to be used for drawings, and watercolours. Old master prints were sometimes printed on vellum, especially for presentation copies, until at least the seventeenth century.

Limp vellum or limp-parchment bindings was used frequently in the 16th and 17th centuries, and were sometimes gilt. In later centuries vellum has been more commonly used like leather. Vellum can be stained virtually any color but mainly it is not, as many people like its faint grain and hair markings.

Many documents that needed to last long were written in vellum as it was able to last longer than paper. Some vellum-written documents are more than a thousand years old.

Modern usage[change | change source]

British Acts of Parliament are still printed on vellum for archival purposes,[5] as are those of the Republic of Ireland.[6] It is still used for Jewish scrolls, for luxury book covers, memorial books, and for various documents in calligraphy.

Today, because of low demand and complicated manufacturing process, animal vellum is expensive and hard to find. Only one UK company still supplies them.[7] A modern vellum-like alternative is made out of cotton. Known as paper vellum, this material is cheaper than animal vellum and can be found in most art and crafting supply stores. Some brands of writing paper and other sorts of paper use the term 'vellum' to suggest quality.

In the artistic crafts of writing, illuminating, lettering, and bookbinding, 'vellum' is normally reserved for calfskin, while any other skin is called 'parchment'.[8]

Paper vellum[change | change source]

Vellum Animal Skin

Paper vellum is made from cotton. Usually translucent, paper vellum in various sizes is often used in applications where tracing is required, such as architectural plans. Like natural vellum, the paper vellum is more stable than paper, which is frequently critical in the development of large drawings and plans such as blueprints.

Storage[change | change source]

Vellum is typically stored in a stable environment with a stable temperature. If vellum is stored in an environment with less than 11% relative humidity, it becomes fragile, brittle, and susceptible to mechanical stresses; if it is stored in an environment with greater than 40% relative humidity, it becomes vulnerable to mold or fungus growth.[9] The best temperature for the preservation of vellum is 20 ± 1.5 °C (68 ± 3 °F)

References[change | change source]

- ↑'vellum - Origin and meaning of vellum by Online Etymology Dictionary'. www.etymonline.com.

- ↑'Differences between Parchment, Vellum and Paper'. National Archives. 15 August 2016.

- ↑'Differences between Parchment, Vellum and Paper'. National Archives. 15 August 2016.

- ↑Young, Laura A. 1995 Bookbinding & conservation by hand: a working guide, Oak Knoll Press. ISBN1-884718-11-6, ISBN978-1-884718-11-3Google books

- ↑'BBC News - UK Politics - Goat skin tradition wins the day'. news.bbc.co.uk.

- ↑'Frequently Asked Questions about the Houses of the Oireachtas - Tithe an Oireachtais'.

- ↑'William Cowley Parchment Makers - Our Parchment & Vellum is used for: Calligraphy and Illumination, Bookbinding, Botanical Art, Heraldic Art, Memorial Books, Drum Making and Lampshades. Bespoke vellum covering service for furniture and wall & door panels. Document printing service for Certificates, Diplomas, Family Trees'. www.williamcowley.co.uk.

- ↑Johnston E. 1906. Writing, illuminating, and lettering; Lamb C.M. (ed) 1956. The calligrapher's handbook.

- ↑Hansen, Eric F. and Lee, Steve N. 1991. The effects of relative humidity on some physical properties of modern vellum: implications for the optimum relative humidity for the display and storage of parchment. The Book and Paper Group Annual.